Convergent Evolution

A Forward-Looking Prediction on "Planetary Science"

Some questions may just be too big for one branch of science to answer. “Are Earth and its life unique?” is probably a good example. While biology, chemistry, cosmology, and many other fields are tangentially related to this timeless question, modern science has developed two disciplines that directly address Earth’s celestial context: “planetary science” (i.e. solar system research) and exoplanet astronomy.

Perhaps surprisingly, solar system and exoplanet research take fundamentally different approaches to studying planetary bodies. The former, what is traditionally called “planetary science,” grew primarily from geology. Breakthroughs typically have come from interplanetary exploration like Voyager 1 & 2, Cassini, and the Curiosity rover. Solar system research is destination-focused; each planetary body is studied as its own unique world.

In contrast, exoplanet research began as an offshoot of stellar astronomy. Even today, most exoplanets are characterized by transits and radial velocities. These methods derive from photometry and spectroscopy, the two fundamental modes of astronomical observing. Progress in stellar astronomy has often come from comparing populations — for example, the Hertzsprung–Russell (HR) diagram — and exoplanet science is no different. We group planets into categories like hot Jupiters and sub-Neptunes. It’s impossible to visit exoplanets, but plotting all the discoveries from missions like Kepler and TESS has revealed trends like the Radius Valley (link).

This historical context is not just an academic curiosity. It manifests at the university, government, and discipline scales. When I was weighing my options for graduate school, I had a burning need to study how planets work. Nonetheless, a senior scientist explained to me that the planetary science and astronomy departments at his university typically obeyed an invisible, yet ponderous boundary: the Oort Cloud. Anything inside the Oort Cloud belonged to the planetary scientists, and astronomers got everything else.

Similarly, NASA and the National Academies break-up their science divisions and their decadal surveys into these distinct fields. From a budget perspective, this structure seems reasonable. Mission architectures and research philosophies are different, hence the two different sets of national priorities in the decadal surveys (link 1, link 2). Nonetheless, this administrative structure means that scientists who want to study planets must sort themselves into one of two groups.

In recent years, however, this academic boundary seems to be dissolving. It’s becoming possible to study exoplanets as geophysical objects and solar system bodies as astrophysical objects. For example, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is finding molecules in exoplanet atmospheres (link) and detecting atmospheres in the process of being destroyed (link). These empirical studies of atmospheric chemistry and long-term stability were previously only possible in the solar system. In asteroid science, the first interstellar objects like `Oumuamua (link) have given us glimpses of exoplanetary material with solar system techniques.

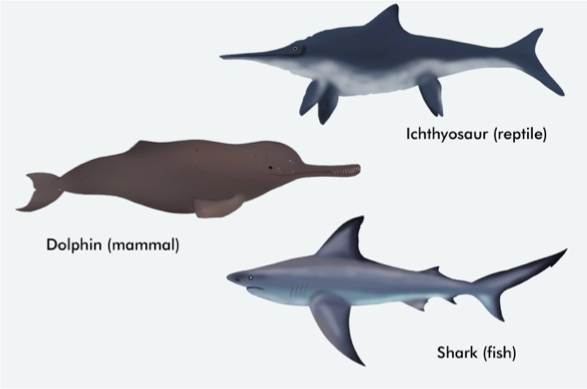

While exoplanet data will always be orders-of-magnitude less precise than solar system data, we’re starting to ask and answer the same questions in both realms. This trajectory seems like the academic analog of convergent evolution in biology, where different organisms sometimes develop similar attributes with similar function. Both insects and birds evolved wings to fly, while both sharks and dolphins evolved streamlined bodies to hunt in the ocean.

Likewise, solar system and exoplanet research are evolving to serve the same academic function; we want to know how planets work from first-principles physics, chemistry, and geology. Our scientific niche is humanity’s desire to address the big questions about our origin and our planet, and this niche is large enough for both solar system and exoplanet research — the holistic understanding of planetary bodies must therefore draw on both lines-of-inquiry. Some fundamental, yet ancient planetary processes only occur on exoplanets in the present day, while the solar system provides a few high-resolution case studies.

While I intend for this blog to focus on “Applied Astrophysics,” bringing the principles of astrophysics to technology, I couldn’t help myself from writing a bit philosophically about a major and ongoing intellectual development. I believe that we may be on the way to redefining “planetary science” as a broadly-scoped, integrated field that researches all planetary bodies, and I am excited to see the results.